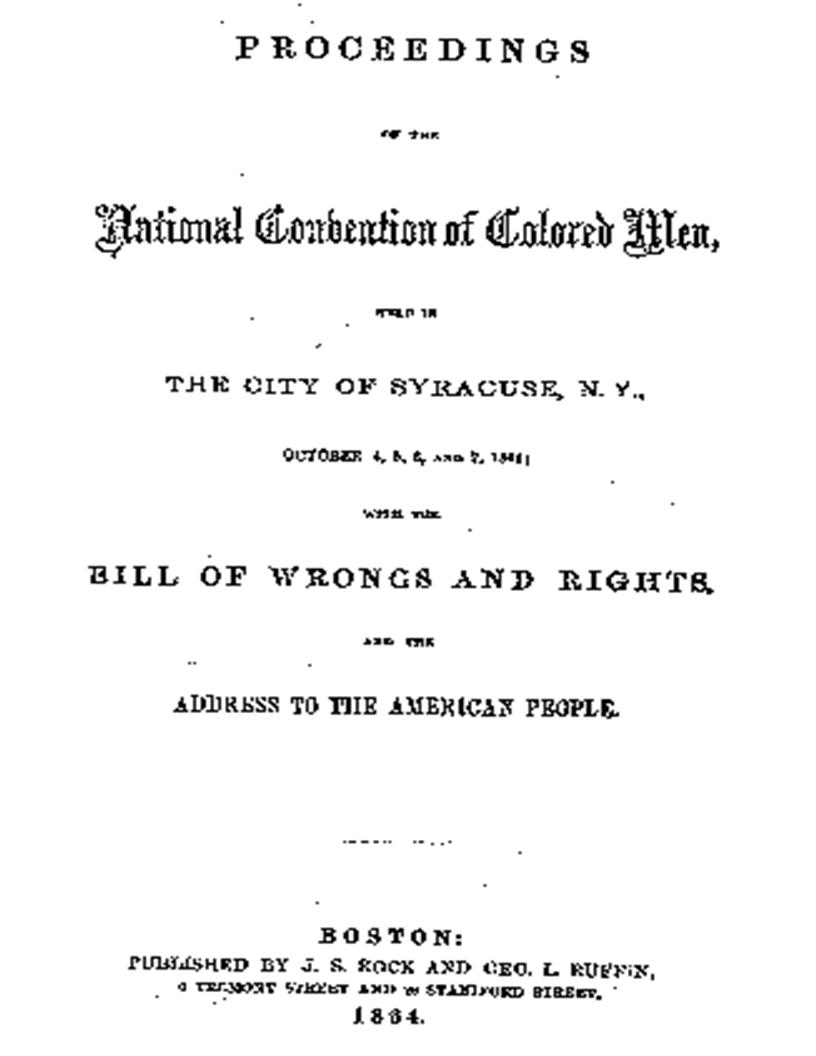

The National Convention of Colored Men took place in Syracuse, New York on October 4th, 1864, almost two years after the Lincoln’s Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, three years after the start of the Civil War, and just a few weeks ahead of the most significant election in the nation’s history. At the time, African Americans could fight in the Union army, and were actively recruited, but could not vote in most regions of the country. Before the event, a promotion for the convention appeared in The Liberator, an American abolitionist newspaper founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp in 1831, on September 9th, 1864, which was written by Frederick Douglass.

During the convention, A Declaration of Wrongs and Rights was produced, outlining the lack of any liberty and the suffering endured by Blacks, both free and enslaved, over hundreds of years in colonial America and the United States. “As a people we have been denied the ownership of our bodies, our wives, homes, children, and the products of our own labor…”

The convention saw one hundred and forty-four delegates attend from eighteen out of thirty five states, including Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Mississippi, Louisiana and Tennessee. Participants included Frederick Douglass, who was the convention president, William Wells Brown, and Henry Highland Garnet.

Douglass said this at the opening of the meeting,

“GENTLEMEN,—I thank you very sincerely for the honor you have conferred upon me, by selecting me from among your number to preside over the deliberations of this Convention. While I am grateful for the position you have been pleased to assign me,—I say it without the least affectation,—I accept it with the utmost diffidence, and distrust of my ability. There are, at least, a score of gentlemen present who could preside better than I can. If you have chosen me because of any belief in my ability to conduct the proceedings of this Convention with special decorum and dignity, I dear you have made a mistake, which will become more and more apparent during the progress of the Convention; but if, as I supposed is the case, you have called me to this position as a mark of your consideration for my labors in our common cause, I am vain enough to admit that the compliment is not wholly undeserved; and, as such, I am grateful for it. For the order and decorum which may prevail here, gentlemen, I look to you. With your assistance and support we shall have harmony, which is essential to our deliberations. The cause which we come here to promote is sacred. Nowhere, in the ‘wide, wide world,’ can men be found coupled with a cause of greater dignity and importance than that which brings us here. We are here to promote the freedom, progress, elevation, and perfect enfranchisement, of the entire colored people of the United States; to show that, though slaves, we are not contented slaves, but that, like all other progressive races of me, we are resolved to advance in the scale of knowledge, worth, and civilization, and claim our rights as men among men. In doing this, we shall give offence to none but the mean and sordid haters of our race; while we shall command the sympathy and encouragement of all me who love impartial freedom, and the welfare of the human race.”