On January 16th, 1919, the 18th Amendment was ratified. The Amendment, which went into effect the following year, prohibited the sale or consumption of alcohol in the U.S.

For the story of prohibition in Syracuse, we turn to OHA’s Research Specialist, Sarah Kozma, and her article, Hello Nellie!: The World of Speakeasies, Bootleggers and Raids in Prohibition Syracuse.

“Hello Nellie!” spoken at a bar today, this probably wouldn’t get you very far, but said at the right bar in 1920s Syracuse, this would have gotten you an illegal alcoholic beverage. Speakeasies, bootleggers, bathtub gin, moonshine; these words conjure up ideas of the Roaring 20s, old gangster movies, exciting car chases, and parties with flappers and dapper dans, but that is only part of the story.

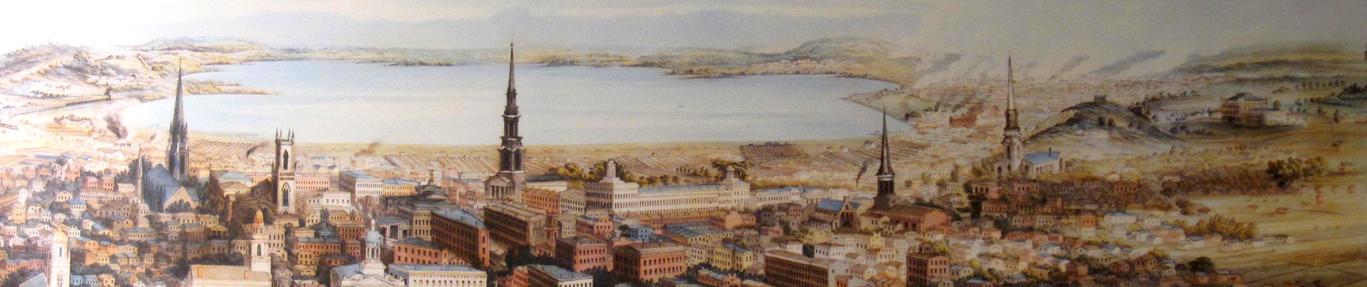

The Temperance Movement, an effort to limit or ban the use of alcohol, with the goal of making society a better place, started in the 1780s. Through the years, the Temperance Movement gained in popularity. From the 1890s-1910, it began appearing on election ballots and states, counties, and towns were given the choice of voting themselves “dry” or “wet.” Dry towns generally forbade or severely restricted the manufacture, sale, and consumption of alcohol, while wet towns had few or no restrictions on alcohol. The ultimate achievement of the Temperance Movement was Prohibition, 1920-1933. Prohibition was, virtually, the entire nation going dry. Syracuse’s Prohibition experience was not unlike other cities, but it was also unique unto itself. The Noble Experiment had begun.

In the early twentieth century, Syracuse and the towns of Onondaga County struggled with the issue of temperance. By 1916, ten of the nineteen towns had elected, by popular vote, to go “dry.” In 1917, there was pressure for the City of Syracuse and the Town of Geddes, particularly the Village of Solvay, to go dry, at least during the time the army camp was at the State Fairgrounds during World War 1. There were petitions “to close all saloons in Syracuse during the Federal Encampment at the Fairgrounds in the ‘interest of public peace, public safety and public morals.’”

All of that became irrelevant in 1919 with the addition of the 18th Amendment to the US Constitution, and the passing of the Volstead Act, also called the National Prohibition Act, which in effect turned the whole country “dry.” It became illegal to manufacture, sell, or transport any alcoholic beverage that had more than .5% alcohol; anything more was seen as an intoxicating beverage, which was under the umbrella of the Volstead Act. On January 16, 1920, the nationwide Prohibition went into effect and Syracuse, like the rest of the country, went dry. This was a problem for Syracuse on more than just a social level. Syracuse had about eleven breweries in operation before Prohibition, but after 1920, breweries everywhere were forced to close or change their product. They were allowed to make a .5% beer, which was called near-beer. This was not, however, what the people really wanted.

Instead of simply going along with the new law, many people found ways to subvert it. Many engaged in home-brewing, while others becoming bootleggers by running their own distillery. Still other people served as rum-runners, smuggling liquor into the States from Canada. However, the most well-known option, perhaps even the most popular, was the speakeasy. Although illegal, speakeasies popped up all over the city, so there were plenty of places where people could get a taste of the illicit brews, but discretion of the location and also of where the alcohol was stored was crucial to avoid heavy fines and even jail time. Speakeasies were often on upper floors of business areas, with a heavy metal door with a peephole. The peephole allowed the doorman to see the potential customers before he let them in. In many places, a password was also required as further security against law enforcement officers. In addition to the speakeasies, illegal drinks could be obtained at certain cafes, former saloons, and hotels with the right password spoken at the bar. Once inside, the speakeasies were often well decorated lounges and stylish clubs, where customers could get a variety of homebrew beers and various liquors. The speakeasies, also called “blind tigers” or “blind pigs,” would generally get their drinks from bootleggers, who made their product in places called “wildcat breweries.” They would also serve a special concoction of the near-beer by injecting alcohol into it using a syringe needle, and selling it as needle-beer.

From the start of prohibition, a federal Prohibition Enforcement Office was established in Syracuse. However, during the first few years, enforcement was lax and raids were random and unorganized. A superintendent of the local Anti-Saloon League of New York explained the problem: “A bunch of wet political leaders have been responsible for the appointment of incompetent and crooked federal agents. Notorious liquor joints have been running wide open, apparently under protection.” However by 1925 the situation had changed – “The house cleaning in the federal office has improved the situation. Some of the worst offenders have been raided and are awaiting punishment. Places that have been running wide open for years have been knocked off. The bootleg underworld in Central New York is in terror. Another year of this kind of vigorous prosecution and bootlegging will be not only unpopular but unprofitable.” [Post-Standard 5-11-1925]

The federal agents had to catch the bootleggers and speakeasy owners in possession of alcohol, which made surprise raids crucial to success. Agents went armed with a search warrant, sledgehammers, axes and crowbars, but sometimes the raids of suspected speakeasies or breweries turned up nothing, possibly because the alcohol was cleverly hidden or perhaps the owners had been alerted to the coming raid. Often it all came down to timing; it was about right time, right place when the bootleggers and speakeasy owners could be caught red-handed.

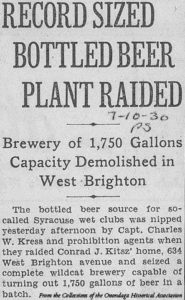

In the late 1920s, there was a crackdown on Syracuse bootleggers and speakeasies with the assignment of experienced agents, like Lowell Smith, aka The Scourge, and Charles Kress, aka the Nemesis of Syracuse. There developed quite a rivalry between these two lawmen and they spurred one another on to best each other in their jobs, which in turn led to an increase in raids and seizures, much to the dismay of the bootleggers. For example, early one morning Smith went out and led three raids on speakeasies and breweries. While Smith was out, Kress was peacefully slumbering until one of his men came and told him what Smith was doing. Kress, not wanting to be outdone, immediately went out and led four raids.

Some of the stories of the raids by the enforcement agents, particularly those of Charles Kress, seem to be straight out of the movies. It was not uncommon for agents to don disguises to infiltrate speakeasies and brewing/distilling establishments. Kress would send an agent, posing as a delivery boy with a package. When the door was opened for him, he was, literally, able to get his foot in the door and then call for the other agents hiding nearby. Other methods included the use of fire ladders to climb through upper story windows and setting up bootleggers while posing as customers. Kress even rode a dumbwaiter into a barricaded part of a saloon to catch out the occupants. At one point the legality of some of his methods were questioned, but after a short suspension he was reinstated.

Bootleggers were quite creative as well, using camouflaged trucks, secret rooms, hidden wall panels, mislabeled packaging, and safes. They did their best to hide their doings, but were not always as successful as they hoped. In 1923, there was a tip given to federal agents regarding a saloon on Burnet Ave. that was allegedly selling liquor. When they showed up they could find nothing to support their suspicion, until they noticed a pipe which seemed slightly out of place. Inside the pipe were two valves, one went to a six gallon tank of gin; the other to the same of whiskey. Needless to say, the proprietor was arrested.

The federal agents did not always win the day. John Miles remembers one such incident regarding Paul Knaus’s restaurant on Park St., from which he served illegal alcoholic beverages. “…Paul received a tip that he was to be raided by Prohibition agents. Paul had a keg of illegal beer on tap and rushed to get rid of it. But rather than spill it down the sewer, he allowed a few regular patrons to roll it across the street and put a tap on it. They were supplied with glasses. When the Prohibition agents showed up they found no illegal booze in Paul’s place but several illegal drinkers enjoying a liquid picnic on the curb across the street. However, since most of the evidence was now gone, the agents apparently felt in no mood to arrest a dozen or so citizens, some of them, we assume, a bit tipsy.” [Syracuse Herald American 5-17-1987]

Many speakeasies were well-known places in their local neighborhoods, as it was often the local neighbors who patronized the establishment. However, this made security and secrecy important for the proprietors. They were wary of newcomers, and the use of passwords, secret knocks, and doormen helped to protect the speakeasies and their clients.

As the crackdown continued the places to sell alcohol decreased, so in the last several years of Prohibition the bootleggers’ rivalry became much more intense, sometimes ending in physical confrontation and destruction of property. Thankfully, Syracuse avoided the full-blown bootleg gang war that erupted in many cities.

By the early 1930s, many Syracusans had enough. The Association Against the Prohibition Amendment was formed in 1930. Anti-prohibition parades and demonstrations were held around the city, many of the protesters, including ex-servicemen, touting the slogan “Prohibition is a failure; It must go!” One particular demonstration in May 1932 involved one of the biggest crowds that had ever gathered in downtown Syracuse. They even stood their ground through two thunderstorms and a hailstorm. The organizers of this parade had invited all the city, county and legislative officials, however only a handful showed up, among them was Syracuse Mayor Rolland B. Marvin.

As support for repeal grew, and with the election of new leadership in Washington, legislation to end Prohibition was introduced. The Cullen-Harrison Act was introduced which, by April 1933, allowed up to 3.2% alcohol, rather than just .5%. Later the Blaine Act was presented, which was a repeal of Prohibition and was passed as the 21st Amendment to the Constitution on December 5, 1933. The Noble Experiment had run its course and ultimately failed.

In Syracuse, no large celebrations were held to welcome the end of Prohibition, although the following day there were quite a few Syracusans out enjoying their new freedom.After prohibition ended many of the Syracuse breweries started up again but it was a long road to recovery and business was never quite the same afterward. In reality, it was the beginning of the end for local breweries.

Prohibition was an era full of contradictions, in Syracuse and around the country. It brought people together, yet it made them suspicious of each other. It was originally supported by a supposed majority, yet a mere thirteen years later it was widely protested. It often changed respectable citizens into criminals. Many neighborhoods rallied around the lawbreakers, keeping silent rather than giving information to the lawmen. It was intended to better society yet criminality flourished. Perhaps this is what makes this era so interesting and unique. Prohibition in Syracuse generated memorable stories, fascinating characters, and had a major impact on its future development.”