Monday Ms. Stories focuses on the women of Onondaga County’s past that many may have either forgotten, haven’t heard of, or don’t know much about.

One of the best-selling books in Syracuse history was written by Mary Shipman Andrews, an author we know little about today. It was called “The Perfect Tribute” and was on Abraham Lincoln and his famous “Gettysburg Address.”

The book, published originally in 1906, “The Perfect Tribute” sold more than 600,000 copies and “was read by millions,” according to Andrews’ obituary. It later became a motion picture and a TV show.

Mary Andrews was an interesting woman, a prolific writer who achieved success while the wife of William Shankland Andrews, an associate judge of the New York Court of Appeals and son of Charles Andrews, once a chief judge of the court. Their son, Paul Shipman Andrews, was dean of the Syracuse University College of Law.

She was born in the South, on April 2, 1860, the daughter of The Rev. Jacob Shipman, an Episcopal rector in Mobile, Alabama, and Lexington, Kentucky. A brother, Herbert Shipman, was an auxiliary bishop of New York. She married William Andrews in 1884.

The Andrews lived on a 56-acre estate they called Wolf Hollow in Taunton, just west of Syracuse. Judge Andrews had the fieldstone main house built in 1912. It was designed by a noted Syracuse architect, Gordon Wright. The name Wolf Hollow came from a local story of wolves gathering in the hollow below the house before it was built.

Mrs. Andrews said the home went up on the spot where her and her husband used to go horseback riding. She described Wolf Hollow as a “dream come true.” The Andrews also had a wilderness camp about 100 miles from Quebec, where they spent summers for 30 years.

Mary qualified as a “big game hunter” by killing seven deer, three caribou and two moose. Her experiences with outdoor activities informed her work and she became known for stories depicting outdoor adventures of boys in hunting, camping and fishing. She published some of these stories in the collections “Bob and the Guides’’ (1906) and “The Eternal Masculine” (1913). She also raised dogs on her estate.

“The Perfect Tribute’’ first was published in Scribner’s Magazine in 1906, and as a stand-alone volume by Scribner’s in the same year. It went through several editions. The editions at the Onondaga Historical Association are marked 1906 and 1922.

“The Perfect Tribute’’ first was published in Scribner’s Magazine in 1906, and as a stand-alone volume by Scribner’s in the same year. It went through several editions. The editions at the Onondaga Historical Association are marked 1906 and 1922.

The story depicts Lincoln writing and delivering the address at Gettysburg and concluding afterwards his speech was an utter failure. The president credited the main speaker at the dedication of the federal cemetery at Gettysburg, orator and U.S. Sen. Edward Everett, with giving the better speech, which went on for about two hours. Lincoln spoke for about two minutes and according to the New York Times report the speech was interrupted five times for applause and was followed by “long continued applause.”

Mary Andrew’s fictional account says “Not a hand was lifted in applause.’’

“A Perfect Tribute’’ continues as Lincoln goes for a walk in Washington the next day and is confronted by a young boy, who tells him his brother, a Confederate captain, lies mortally ill in a nearby prison hospital and wants to speak to a lawyer about drawing a will. Lincoln goes to the hospital and sees the dying man, who does not recognize the president. The soldier praises the Gettysburg address as “one of the great speeches in history.’’

He dies with his hand and the president’s entwined.

In a Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association article in 2004 Kent Gramm takes issue with the facts of Andrews’ story, including the notion that Lincoln wrote the address hurriedly on the train on his way to Gettysburg. He concluded her book was “a perfect tribute that never happened.’’

Nonetheless the story was very popular and was assigned for reading to generations of American school children. One source says Mary Andrews got the story from a member of the Burlingame family, who got it from Edward Everett, the featured speaker at Gettysburg.

Mrs. Andrews was said to consider Lincoln a national hero. She also wrote of him in two other books, “White Satin Dress,’’ and “The Counsel Assigned.’’

She explained she’d been interested in writing since she was a girl, abandoning the idea of becoming a portrait painter. She earned her first check as a writer – $75 – during her “courtship year” for a story submitted to Scribner’s Magazine at the urging of William Andrews in 1902. This was a story titled “Crowned With Glory and Honor.’’

In information about herself sent to students at Nottingham High School she explained that she considered the business of writing as “the most entrancing fun invented – that and riding a horse.’’ She said she had no illusions about her place in the ranks of literature: “I feel myself one dangle on the fringe of that shiny garment.’’

In another interview, she said she did her best work in the morning, in a galley off of her bedroom and at a cottage workshop secluded in the woods of Wolf Hollow, where no one would come “bounding in.” She also wrote during her summers vacationing in Quebec.

Critics said Mary Andrews was best known for her sentimental and melodramatic magazine fiction. Her 20-odd books included “A Good Samaritan,” “A Joy In The Morning” and “A Lost Commander,” a biography of Florence Nightingale, published in 1929, one of her last books.

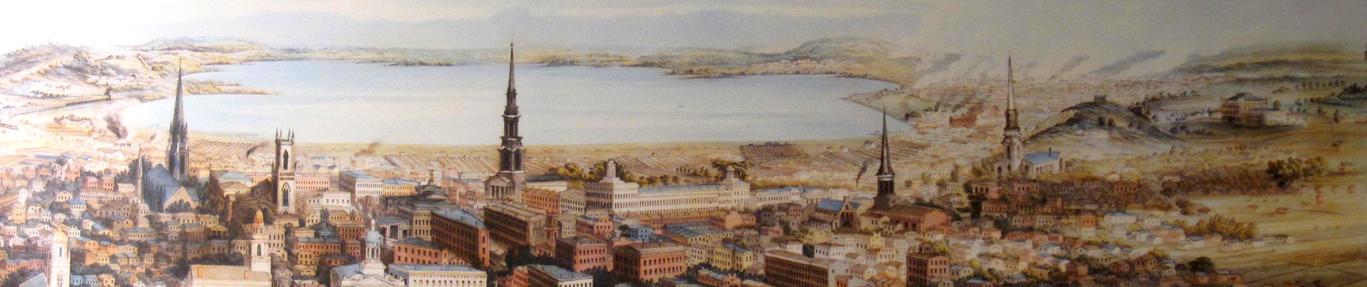

Mrs. Andrews also is credited as the author of a frisky account of the centennial of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church of Syracuse, in 1924, “From Generation to Generation.” The book carries a dedication to her father-in-law, Judge Charles Andrews, who was senior warden of the church. He died in 1918. (Judge Andrews also served as mayor of Syracuse and Onondaga County district attorney.)

“The Perfect Tribute” was adapted into a short film starring Chic Sale as Lincoln and a 1991 television movie starring Jason Robards as the president. Two of Andrews’ other works were adapted for film: “The Courage of the Common Place” in 1917 and “Three Things’’ as the “Unbeliever” in 1918.

Mary Shipman Andrews died Aug.2, 1936. Her obituary in a Syracuse newspaper called her a “prolific pen woman,” as well as “one of the nation’s foremost writers.’’ Her husband, retired Judge William Andrews, died three days later of injuries received while reaching for a glass of milk in his bedroom at Wolf Hollow. Their funeral services were held together.

The Wolf Hollow property was sold to Wolf Hollow Development Corp. in 1958 and the portion along Terry Road was subdivided for homes. Gwynn Morey, a long-time resident of Taunton, says the land originally was part of extensive Fay family holdings. He says Mary Shipman Andrews’ writing cottage near the main house is no longer there but the main 1912 house still stands and is privately owned. The Andrews family had a large garden on the estate, as well as an apple orchard. The hand-hewn stone for the three-story main house came from the Split Rock quarry nearby.

According to a description of the main house written for an historic tour sponsored by Town of Onondaga Historical Society in 1993 the interior was remodeled in the 1930s but the exterior is unchanged. Adjoining the house are the original carriage house and stable. Features of the interior include heavy oak woodwork and trim hand-carved by Judge Andrews. Also, there are a sweeping stairway in the center hall, 12-foot ceilings and ornate fireplaces in each room.