Gustav Stickley, born on this day in 1858 (he passed away in 1942) grew up in the Mid-West, but lived much of his adult life in Syracuse. His promotion of the “Craftsman” style is most associated with furniture, but he also was a passionate advocate for complimentary forms in architecture. He published several plans in his magazine, The Craftsman, from 1904 to 1915. And versions of many were built across the country.

During this era, when many novel approaches to art were being explored both in Europe and America, Stickley was not the only proponent of a radical break from traditional, ornate residential architecture. In places like Chicago and Buffalo, Frank Lloyd Wright was also opening eyes to new architectural forms with his “Prairie School” house designs.

Stickley was interested all facets of the decorative arts, and that was reflected in The Craftsman and its articles, which included American painting and art. Interestingly, a 1906 story extolled artists who painted particularly American scenery rather than copying the colorful, flowery work of French Impressionists, which the article referred to as a “blight.”

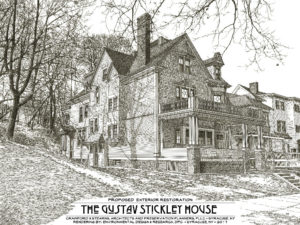

Restoration is underway at his Columbus Avenue house in Syracuse ‘s Westcott neighborhood, and we’re excited to share an artist’s rendering of the restored exterior. We encourage you to visit there website often to follow the progress. You can also learn about the history of the house here.

Learn more via the Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms

Gustav Stickley, the eldest son of first generation German immigrants Barbara and Leopold Stoeckel, was born March 9, 1858 in Osceola, Wisconsin. Originally named Gustave Stickley, he dropped the “e” from his name around 1903. When his parents separated in 1869 his formal education ended at sixth grade and he began training as a stonemason. By the age of 12, young Gustave was employed as a stonemason helping to support the large family. He moved with his mother and some of his siblings to Brandt, Pennsylvania about 1875, and began working at an uncle’s chair factory, where he soon rose to manage it.

In 1883 he and his brothers Albert and Charles founded the Stickley Brothers Company in Susquehanna, Pennsylvania. That same year he married Eda Ann Simmons and a year later the brothers moved their operations to Binghamton, New York. By 1898 he had his own furniture business, The Gustave Stickley Company, in the Eastwood suburb of Syracuse, New York.

In 1895 he traveled to Europe for the first time and a transformation began. He saw the products of the English Arts and Crafts movement and the French Art Nouveau. A year later he made a second trip to England and the Continent. These trips awakened a spirit deep inside him. The Arts and Crafts movement in Europe was movement promoting well built, hand crafted, and honest work. The movement was connected to a backlash against the poor treatment of workers in the urban factories. He embraced many of the ideas of this new Movement with a passion and was filled with ideas to apply its concepts in his furniture business.

Working with architect and designer Henry Wilkinson and, later, designer LaMont A. Warner, he created his first Arts and Crafts works in an experimental line called the “New Furniture” and, after exhibiting the designs in the Grand Rapids trade show in July 1900, he arranged for the Tobey Furniture Company of Chicago to distribute the line. These designs were a radical departure from the furniture of the Victorian era. They reflected the Arts and Crafts ideals of simplicity, honesty in construction, and truth to materials. Unadorned, plain surfaces were enlivening by the careful application of colorants so as not to obscure the grain of the wood and mortise and tenon joinery was exposed to emphasize the structural qualities of the works. Hammered metal hardware, in armor-bright polished iron or patinated copper, emphasized the handmade qualities of furniture which was fabricated using both hand-working techniques and modern woodworking machinery.

At the very end of 1900, Stickley rented the famous Crouse stables in Syracuse, which he used as executive offices and a showroom for his products, renaming it the ”Craftsman Building.” There he could offer middle class consumers a host of progressive furniture designs in ammonia-fumed quarter-sawn white oak.

In 1901, perhaps because his firm did not receive the name recognition he craved, he dropped his relationship with Toby and changed the name of his firm to the United Crafts. The name implied that his factory was a worker’s cooperative, but he was still the owner and employer.

Later that year he launched The Craftsman magazine, with Syracuse University professor Irene Sargent as editor. In the magazine, Sargent first focused on the early work of William Morris and John Ruskin in England. As the magazine matured it broadened its coverage to include homes and home crafts, literature and music, architecture, city planning, social conditions and progressive political issues. He was an early and strong supporter of conservation issues. Stickley was certainly not a socialist, but he seems to have been interested in some of the concepts, including the Women’s movement and particularly the ideas involving fair treatment of employees. He did try using profit sharing with his employees, but ended the practice in 1904.

The Craftsman became the “Bible” for promoting the Arts and Crafts philosophy, as well as his products and, through advertisements, for a range of products of interest to the homemaker. But it was also a magazine of romance and dreams, where he could urge readers to escape their busy lives and dream of simpler times and a better world. Readers were encouraged to find pleasure in manual tasks like gardening and the creation of handcrafted work. He even published plans on how to make his furniture designs in the reader’s own workshop.

Stickley also became quite interested in architecture. He began publishing house designs by various architects (the illustrations featured his furniture prominently!) in 1902. Stickley offered to answer reader questions on the design of an Arts and Crafts style home. Stickley’s architectural ideas were delineated by the talented individuals whom he employed, including Wilkinson, Warner and famed architect Harvey Ellis, who worked with Stickley through the latter half of 1903. Ellis also had an immediate and profound effect upon the design of The Craftsman magazine and the furnishings Stickley was producing, reinforcing the connections between Stickley’s work and that of English and European designers. During 1903, Stickley’s furniture evolved from solid, monumental forms to some lighter shapes, relieved by arches, tapering legs, and in a new experimental line, inlay as decoration.

In November 1903, Stickley announced the “Home Builders Club” in his magazine. Beginning in 1904, any subscriber was eligible to receive a free set of house plans on homes that would be designed and published each month in the magazine. By the time The Craftsman ended publication in 1916, there were more than 222 different home plans available to Stickley’s subscribers, and his “Architectural Department” would modify an existing design or create new homes on commission. The homes were offered in a number of types familiar to the American public —the farmhouse, four-square, town house, cottage, and bungalow, among others. A house should be constructed in harmony with its landscape, using natural materials. Soft earth-toned colors predominated and interiors included simplified moldings, stained wood, and characteristic features such as built-in cabinets and fireplaces with inglenooks for seating. Although these homes were not always innovative in terms of progressive style, designs reflected current approaches to open floor plans, economy of function, and use of novel materials for walls, roofs, and surface treatments. He encouraged built in benches, bookcases and sideboards to create a practical house, independent of total reliance upon furniture to make it useful and appealing. Groupings of windows allowed ample light inside and appealing views of the outside.

Also in 1903, he changed the name of his company again, to The Craftsman Workshops and marketed his product with the brand name “Craftsman,” and ultimately over 100 retailers across the United States represented the brand.

In what was probably a sound business decision in order to become a national “player,” Stickley moved his magazine, architectural department, marketing and sales operations to New York City in 1906. However, his family continued to live in Syracuse and he had to travel to Syracuse to visit them, as well as his factory.

In 1908, he began to purchase tracts of farmland in near Morris Plains, NJ. This property would become known as Craftsman Farms. His wife Eda and their six children, Barbara, Mildred, Hazel, Marion, Gustav Jr. and Ruth would join him there in the spring of 1910. For a short time Stickley had succeeded in all his dreams. He was a nationally known tastemaker, his family was gathered around him at his country estate and his products were famous world-wide. His magazine had achieved highly competitive circulation numbers.

But, as a believer of the Arts and Crafts as a way of life, Stickley over-reached. He leased a new and excessively expensive 12-story headquarters building in mid-town Manhattan — the Craftsman Building — beginning in 1913, only a year before the outbreak of World War I, just as his company began to operate at a loss, and just as interest in the Arts and Crafts movement was beginning to wane and competition was increasing, even from his own brothers.

Leopold and John George Stickley had begun the firm of L&J.G. Stickley down the road from Eastwood in Fayetteville, NY, in 1905 and had become quite successful, making quality products that rivaled their older brother’s. Albert (along with JG for a time) had established Stickley Brothers Co. in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1891 and they too offered a line of Arts and Crafts furniture. And finally brother Charles, who had stayed in Binghamton, sold competing furniture from his factory also.

In 1915 Stickley filed for bankruptcy — he owed nearly a quarter of a million dollars, The Craftsman ceased publication by the end of 1916, and he was forced to sell Craftsman Farms in 1917 to stave off foreclosure.

In an attempt to rescue their older brother, the other Stickley brothers formed Stickley Associated Cabinetmakers, absorbing The Craftsman Workshops.

Gustav Stickley moved back to Syracuse, where his wife was paralyzed by a stroke. She died in 1919, and after her death he moved in with his daughter Barbara and her husband, who lived in the home he had built for his family in Syracuse in 1900. There he lived, except for long absences visiting his other children, until he died on April 21, 1942.

Known today as the creator of Craftsman furniture, made of quarter-sawn white oak in subtle, plain designs, he was much more than a furniture maker. He was a visionary spokesman and proponent for the Arts and Crafts philosophy and a major tastemaker of his era.

By Ray Stubblebine

This brief biography relied on David Cathers monograph Gustav Stickley, published by Phaidon and Gustav Stickley, The Craftsman by Mary Ann Smith, published by Dover.