By Richard G. Case

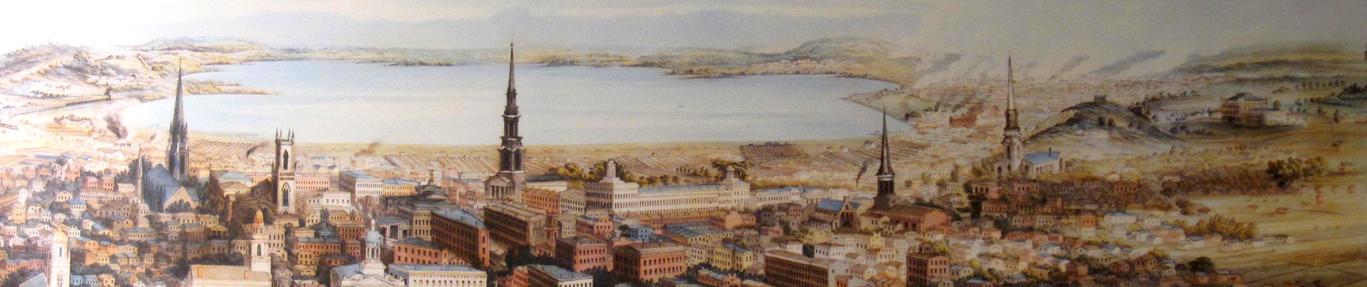

“Back in the day, in 1999 when I still wrote for the Syracuse Post-Standard, the word “Syracuse’’ jumped out at me as I read an obituary in the New York Times for Helen Aberson Mayer, at 91.

The by-lined death notice said Helen wrote the story that inspired the 1941 Walt Disney film, “Dumbo.’’

It also said this happened when Helen, a Syracuse native, still lived in Syracuse.

Who knew? I asked myself. A few phone calls convinced me the answer was: this is a fragment of our history not too many people in Syracuse know about. I had a story for my column. Almost a year later, the yarn of Dumbo’s creation – “Still Flying” – was published as the cover story in the Post’s Sunday supplement, Stars magazine.

This is how it unraveled. . . .

Helen Aberson was born in Syracuse in 1907, the daughter of Anna and Morris Aberson, Russian immigrants to our town. Morris Is listed in city directories as a cigar maker and grocer. The family lived at 1307 East Genesee St.

She attended the Syracuse University School of Speech and graduated in 1929. In a questionnaire she returned to the university’s Alumni Office in 1939, she wrote “I went to New York after graduation and did social work. Returned to Syracuse in 1933 to direct dramatic activities at a nearby children’s camp (also took a job as director of dramatic activities for the municipal recreational department. I left in August 1937 to do radio work for a local concern.’’

Her niece, Jeanne Castle of Little Falls (the daughter of Helen’s brother, Sim Aberson) told me she believes Helen worked at WSYR, a Syracuse radio station, adopting the name of “Barbara Manning.’’ She listed her occupation as “radio commentator” on the Alumni Office form.

Helen continued on the form she sent to the Alumni Office, speaking for the first time of her first husband, Harold Pearl, her collaborator on the Dumbo story:

“I met my husband through business. He’s an ex-New York American newspaper man who had come to Syracuse as an exploitation and publicity man for United Artists. He stayed on after being offered the managership of a downtown Syracuse theater (The Eckel.)

“We met in October 1937. I became Mrs. Harold Pearl on Feb.14, 1938. (We couldn’t resist St.Valentine’s Day.) We collaborated on a children’s story, which is to be published soon. Writing is a hobby at present but we hope to turn it into a full-time job some day. We’re headed to New York right now and eventually the Coast – we hope.’’

The Pearls divorced in the summer of 1939. Helen’s son of her second marriage, Andrew Mayer of Staten Island, told me that his mother explained to him that Harold Pearl returned to New York City after the divorce and died years before Helen.

In 1944, Helen married Richard J. Mayer, a former Wall Street Journal columnist and commodity editor she met while working for the Office of War Information in Washington during World War II. He survived her in 1999.

There’s a hint in a 1939 Herald-Journal newspaper story of the high hopes that Helen and Harold had for “Dumbo” back then. The film was released in October 1941. “Two Syracusans, Helen and Harold Pearl, had one of their children’s stories, ‘Dumbo, the Flying Elephant,’ purchased by Disney Productions. ‘’ A headline above the story read “Headed for Fame and Fortune.’’

- Dumbo Book Cover 1941

- Dumbo Book Cover 1947

- Dumbo Book Cover 1968

- Dumbo Book Cover 1988

It didn’t turn out that way. The Pearls originally sold the rights to their manuscript to a Syracusan, Everett Whitmyre, who apparently originated the idea of a Roll-a-Book, a book designed to be scrolled through, as a sideline to his work as an advertising agent. To this day, we don’t know if “Dumbo’’ ever was published as a Roll-a-Book, although a proof of the manuscript exists in the papers of Helen Durney, a Syracuse artist who drew a series of illustrations for the “Dumbo’’ original.

Helen Mayer explained that transaction in more detail in a letter she wrote to a lawyer in 1993: “In 1938, my ex-husband (now deceased) and I wrote a story about a little elephant with very big ears who used them to fly. We named him Dumbo.

“We approached a local publisher in Syracuse, New York – then my home town – to print the books. He said rather than printing a small number of books, we ought to send our manuscript to Walt Disney to be used for a movie. We thought it was a wild idea but went along with it. The very next day we had a call from the Disney people with an offer to buy our manuscript for $1,000 and they would publish it and make it into a movie.”

The Disney film followed the original Aberson-Pearl story, but details were changed and added. For example, the authors called the mom of Dumbo “Mother Ella.’’ Disney renamed her “Mrs. Jumbo.’’ The Syracusans made up a helper for their little elephant. He was a wise robin. They called him “Red.’’ Disney turned him into a mouse named “Timothy.”

Helen Aberson traveled to California as a consultant on the film. Her son, Andrew Mayer, said her heard various stories about his mother’s experience in California, but he sensed his mother returned home unhappy with some of the changes Disney made in her story. “She was the sort of person who tried to see the sun in the clouds,’’ Andrew explained.

“She never said exactly, but I know she felt she was not treated well,’’ he continued. “She was upset about the manner in which her name was excluded” from the credits of “Dumbo” book Disney brought out in concert with the movie. This happened when the original Roll-a-Book copyright expired in 1986.

The rights the Pearls sold to Disney included a series of Disney Golden Books still in print since the first in the 1940s. Andrew Mayer thinks his mother earned about $1,000 from her creation.

The “Dumbo’’ project had a third collaborator in Syracuse, artist Helen Durney, who graduated with a degree in painting from Syracuse University in 1927. Miss Durney, who died here in 1970, left only cousins, as far as we know. Unfortunately, we don’t know her feelings about the “Dumbo’’ film and her relations with the Disney company. The movie was not mentioned in her obituary.

A box of Helen Durney’s papers, including drawings and letters relating to “Dumbo,’’ was found in Chittenango after her death. Those documents were donated to the Syracuse University library archives.

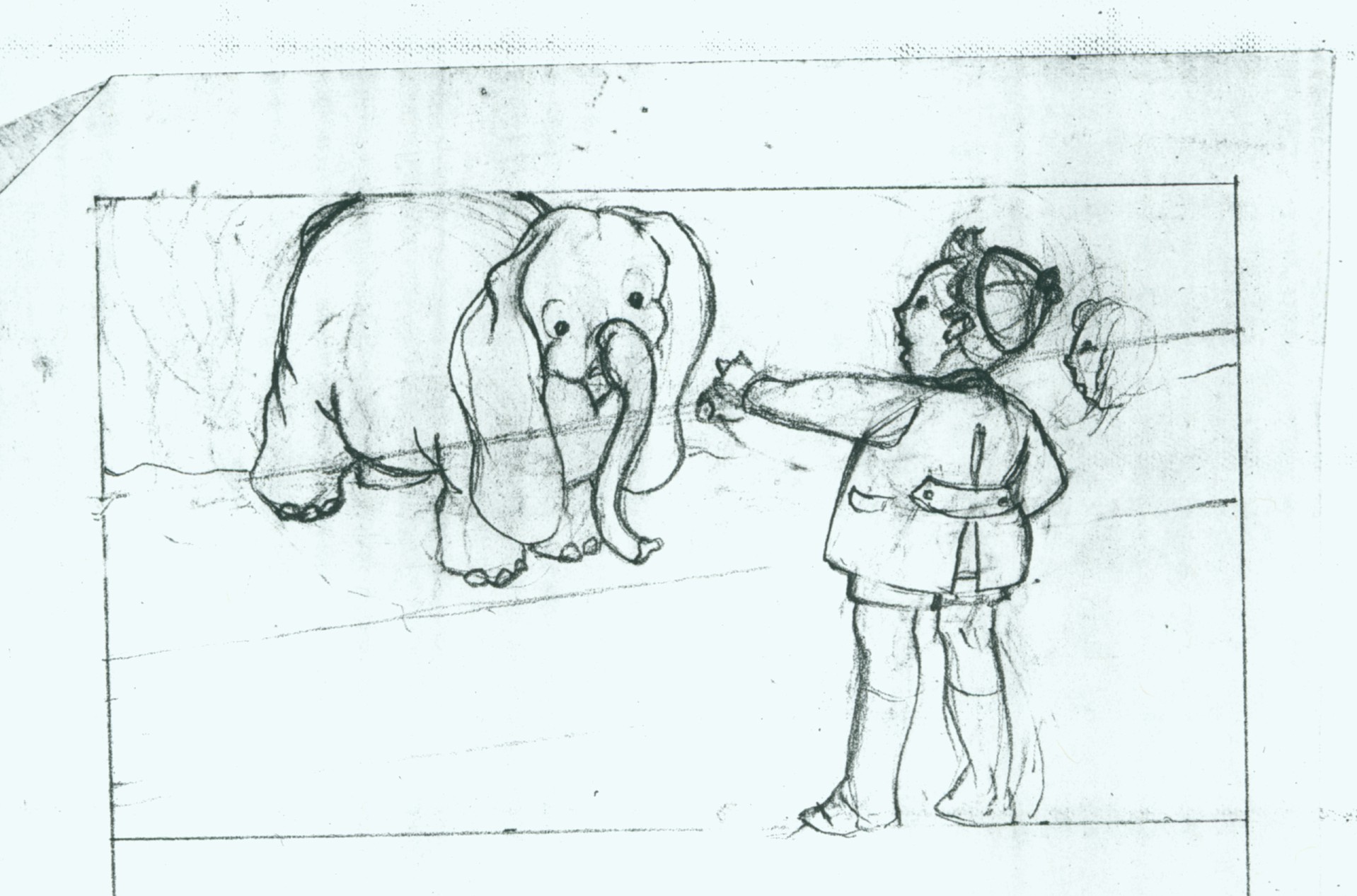

- Dumbo Illustration by Helen Durney, original located at SU Special Collections

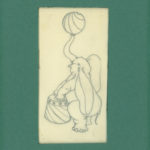

- Dumbo Illustration by Helen Durney – cover for Roll-A-Book. Original located at SU Special Collections

- Original Dumbo Illustration by Helen Durney.

- Dumbo in Roll-A-Book format

- From Walt Disney

Helen Durney apparently had a career as an artist and patron of the arts. We don’t know how she connected to the Pearls. In a letter in the Disney archives, written in 1939 to “Walter Disney,’’ Helen said “I have lived with him (Dumbo) since last February when he took form in one antic after another on tracing paper. From these many rough sketches, Mr. (Everett) Whitmyre of Roll-a-Book picked the final sixteen for illustrations, which were finished in pen and ink.”

There is a vein of sadness in the letter. Helen appears to be asking Walt Disney for a job. She wished him luck on the new film (“Dumbo’’ was released in 1941), adding these lines: “The world is so much richer place because you live, Walter Disney. Don’t let anything happen to your creative genius. Don’t ever grow up.’’

In the master’s reply, from the company archives, Disney said “As you predicted, he has proved to be a swell little character to work with, and we are having a lot of fun making the picture.’’ He did not offer her a job. Biographers of Walt Disney claim the “Dumbo’’ movie saved the small, struggling company from financial ruin.

Her obituary said Helen Durney “worked for the Knopf Publishing Co. in New York City for several years.” She also served as educational and publicity secretary at the Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts, now the Everson Museum. The museum exhibited some of her “Dumbo’’ drawings in 1939. In a talk she gave at the museum that year, Helen credited Everett Whitmyre with inventing the Roll-a-Book concept while watching children at the New York Public Library. “Without Mr. Whitmyre, there would have been no Dumbo,’’ Helen said.

Andrew Mayer believes his mother, also Helen, once had a copy of the “Dumbo’’ book, which readers turned using a small knob. He said Helen Mayer’s trunk of “Dumbo’’ memoriablia had been lost by the family. There is a printer’s proof of the book, as written by the Pearls, in Helen Durney’s papers at SU.

Press materials distributed by Disney for the 60th in 2001 stated that a sequel, “Dumbo II,’’ was in production, scheduled for release in 2004. It has not appeared, so far.

Footnote: Ever the curious reporter, I tried to follow the path of Helen Durney in 1999. Two of her cousins were mentioned as survivors in her brief obituary in 1970. One of her cousins was a Mrs. Andrew Anguish of Chittenango. It turned out that both Mrs. Anguish and her husband had died, too.

I called my friend, the late Clara Houck, a native daughter and historian of Chittenango. Did she know the Anquishes? She did. She also knew their neighborhood, Arlene Baird, had looked after them and helped settle their estate, when Andrew died in 1996. Why not call Arlene? Clara suggested.

I did and stood on Arlene’s glassed-in porch a few days later, listening to her story about having the power of attorney for Andrew Anguish and helping to clean out the house after his death. She said she’d come across a box of the papers of Helen Durney. She was tempted to trash them but had second thoughts. After all, Arlene reasoned, someone must have cared for them all these years. She knew Helen Durney was an artist; the papers must be connected to her career.

“I guess they were saved for a reason,’’ Arlene said.

Arlene agreed with me that the papers, stuffed into a Syracuse department store suit box, ought to be donated to Syracuse University, where both Helens, Durney and Aberson, had graduated. Two months later, Arlene Baird herself died.”