On May 22, 1915, after a five-week trial, the William Barnes vs. Theodore Roosevelt libel suit ended. Barnes, a former chairman of the Republican National Committee, had sued Roosevelt for $50,000 for an alleged libelous statement in which Roosevelt had referred to Barnes as a corrupt political boss. More specifically, he publicly called Barnes “a political boss of the most obnoxious type.” Roosevelt’s defense was to prove that his statement was indeed true. The trial was moved from Albany, the State capital, to the courthouse in Syracuse as it was a more neutral location.

The trial did not begin well for the former President. While he admitted to his son, Kermit, that the judge was fair—if a bit legalistic—he was frustrated by the proceedings as a whole. While on the witness stand, the uncontainable former president said whatever he wanted. Not even the lawyers’ objections or judge’s gaveling could stop him. After two days of deliberations, the jury returned a unanimous verdict in favor of Roosevelt.

Want to learn more? You can read Barnes vs. Roosevelt: Theater in the Courtroom By Hon. Stewart F. Hancock, Jr. by clicking below

Barnes vs. Roosevelt: Theater in the Courtroom

“I’m going to Syracuse tomorrow to nail Roosevelt’s hide to the fence.” So said William Barnes, once the most influential Republican in New York, to Elihu Root on the eve of the trial of Barnes’ historic lawsuit against Theodore Roosevelt. Root reportedly replied: “ I know Roosevelt, and you want to be very sure that it is Roosevelt’s hide that you get on the fence.”

Barnes was heading to Syracuse for the trial of the libel action he started based on statements Roosevelt had made accusing him of political corruption. But what would open the next day, April 19, 1915, in Supreme Court, Onondaga County, was much more than a libel trial. It would be the deciding round in a bitter public struggle between two powerful men for control of New York’s Republican Party. The hide-on-the-fence metaphor was apt.

Until a few months before the trial, William Barnes had ruled the New York Republican party as Chairman of the State Committee. He owned and published the Albany Evening Journal , Albany’s leading newspaper, operated a lucrative printing business, and instinctively shared the conservative outlook of his party’s financial backers. As a lifelong Republican regular and a grandson of Thurlow Weed, one of the founders of the Republican Party, Barnes stood for government through the party system and loyalty to the organization. A big man, obviously fond of his expensive suits, he looked something like a pompous chairman of the board.

Theodore Roosevelt and William Barnes had similar backgrounds. Like Barnes, Roosevelt had graduated from Harvard and belonged to a prestigious New York family. The two men knew each other well and had once been friends. Both were proud, egotistical and accustomed to power. In appearance and demeanor, however, they were quite different; in their political philosophies, exact opposites.

Roosevelt, only 56 years of age, an ex-President of the United States, a former Governor of New York, and the leader of the charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill, had commanding presence and boundless charm. Although officially retired from politics when Taft succeeded him in the White House in 1909, the “Colonel”, or “T.R.”, or “Teddy”, as Roosevelt was affectionately known, still had vast appeal as a national hero. The accounts of his hunting safaris had kept him in public view as a man of action. He exuded the vigor and self-assurance of a natural leader.

Roosevelt was by no means inexperienced in the art of backroom political manipulation. But he had built his reputation as the one-time Police Commissioner of New York, the co-founder of the Anti-Saloon League, the author, the explorer, the naturalist, the high-minded intellectual, the military hero, and the crusader against crime, corruption, and the big trusts. His image was that of the no-nonsense reformer who wanted to remake the political process and rid it of its evil ways.

When Barnes and Roosevelt entered the packed court-room on April 19th before Justice (later Court of Appeals Judge) William S. Andrews and a small town jury of farmers, artisans and shopkeepers, it was to settle for all time what The Post Standard had heralded as one “of the greatest political contests in the history of the United States.” As The Journal put it that evening, “now the gladiators meet upon the common battlefield of the law.” What had brought them to this impasse?

Their rivalry and dislike, which had long simmered beneath the surface, erupted as a public dispute at the 1910 State Republican Convention. Still young and ambitious after returning from his African big game safaris, but out of the office and the glare of the limelight which he loved, what was this popular former President to do? For Roosevelt, there was only one answer. He would simply pick up the political career which he had put aside when he backed Taft for the White House in 1908 and run again, himself, as the Republican presidential nominee in 1912. And what better way to start rebuilding his power base and influence than by taking control of his own State’s party from Chairman Barnes and the entrenched Republican regulars? At the 1910 State Republican convention, Roosevelt got his candidate, Henry L. Stimson, nominated for governor, soundly defeating the choice of Barnes and the State Committee. Furious, Barnes resigned as Chairman. That fall when Stimson lost the election to the Democrat John A. Dix, Barnes not surprisingly, put the blame on Roosevelt.

In the next round, at the 1912 Republican National Convention in Chicago, Barnes got even. The oldline conservatives, who supported Taft, held off a spirited challenge by the progressive Republicans in one of the bitterest floor fights in political history. Roosevelt’s bid for the nomination was rejected and Taft renominated. Angered by his defeat and determined to carry his fight against Taft and the conservatives to the people, Roosevelt formed his own “Bull Moose” Party and ran as its candidate. He drew more votes than Taft but the party split resulted in Woodrow Wilson’s election. Roosevelt blamed Barnes for his defeat at Chicago – and with good reason. Barnes, who had again assumed control of the New York Republicans as State Chairman, had been one of the dominant powers as a convention delegate and a prominent member of the National Committee. He had openly led the fight for Taft’s renomination.

The third round – the clash that put the breach beyond any hope of repair and led to the libel suit – took place at the Republican State Convention at Saratoga Springs in the summer of 1914. There, Roosevelt tried, without success, to repeat what he had done in 1910: nominate his own man for governor (at this time, Harvey D. Hinman) over the opposition of Chairman Barnes and the regular Republicans.

The lawsuit stemmed from a press release that Roosevelt issued as the advocate of party reform in his aborted campaign to oust Barnes from control. In the release, Roosevelt allegedly libeled Barnes by portraying him as a corrupt political “boss.” He charged that Barnes had acted in a clandestine alliance with his counterpart in the Democratic Party, State Chairman and Tammany Hall leader Charles Murphy. These two leaders, he said, had for years manipulated the machinery of the State government to the detriment of the people and solely for the personal political benefit of the two corrupt conspirators. “The state government is rotten throughout in almost all its departments” Roosevelt had written, “and this is directly due to the dominance in politics of Mr. Murphy and his sub-bosses – aided and abetted when necessary by Mr. Barnes.” “These bosses,” Roosevelt went on, “form the all-powerful invisible government which is responsible for the maladministration and corruption in the public offices of the state. These machine masters secure the appointment to offices of men, whose activities so deeply taint and discredit our whole governmental system.”

There is no question that the statements were defamatory; calling someone a corrupt political boss is libel per se. Roosevelt conceded, indeed boasted, that he had made the statements and that they referred to Barnes. His defense was simple and direct: what he said was true and he would prove it. In effect, Barnes was the defendant and Roosevelt the plaintiff.

At stake were the political fortunes of these two men. Barnes wanted to shore up his declining influence in the State and run for U.S. Senator. To do this, he had to convince the jury that Roosevelt’s charges were false. Roosevelt, his power diminished by the defeats at the Chicago convention and in the 1912 Presidential election, wanted to regain his former stature as the national leader of the progressive wing of the Republican Party. He had to start in his home state, New York, and to do that he needed to destroy Barnes – the epitome of the machine pol- by proving the truth of his charges. One think was certain: when the jury returned its verdict, someone’s political hide would go on the fence.

Ever since the preceding November, when the Appellate Division changed the venue from Albany County to Onondaga County to place it in a fair and neutral locale, the national newspapers had been playing up the forthcoming trial as the political event of the year. For the local press, it was the story of the century. Syracuse’s three dailies made the most of it. For weeks prior to the trial, they had been building up the suspense. As the trial approached they capped it off with headlines such as “BARNES – ROOSEVELT PREPARED FOR BATTLE” and were happily answering their readers’ demands for the latest news on the trial by selling them two or even three extras a day.

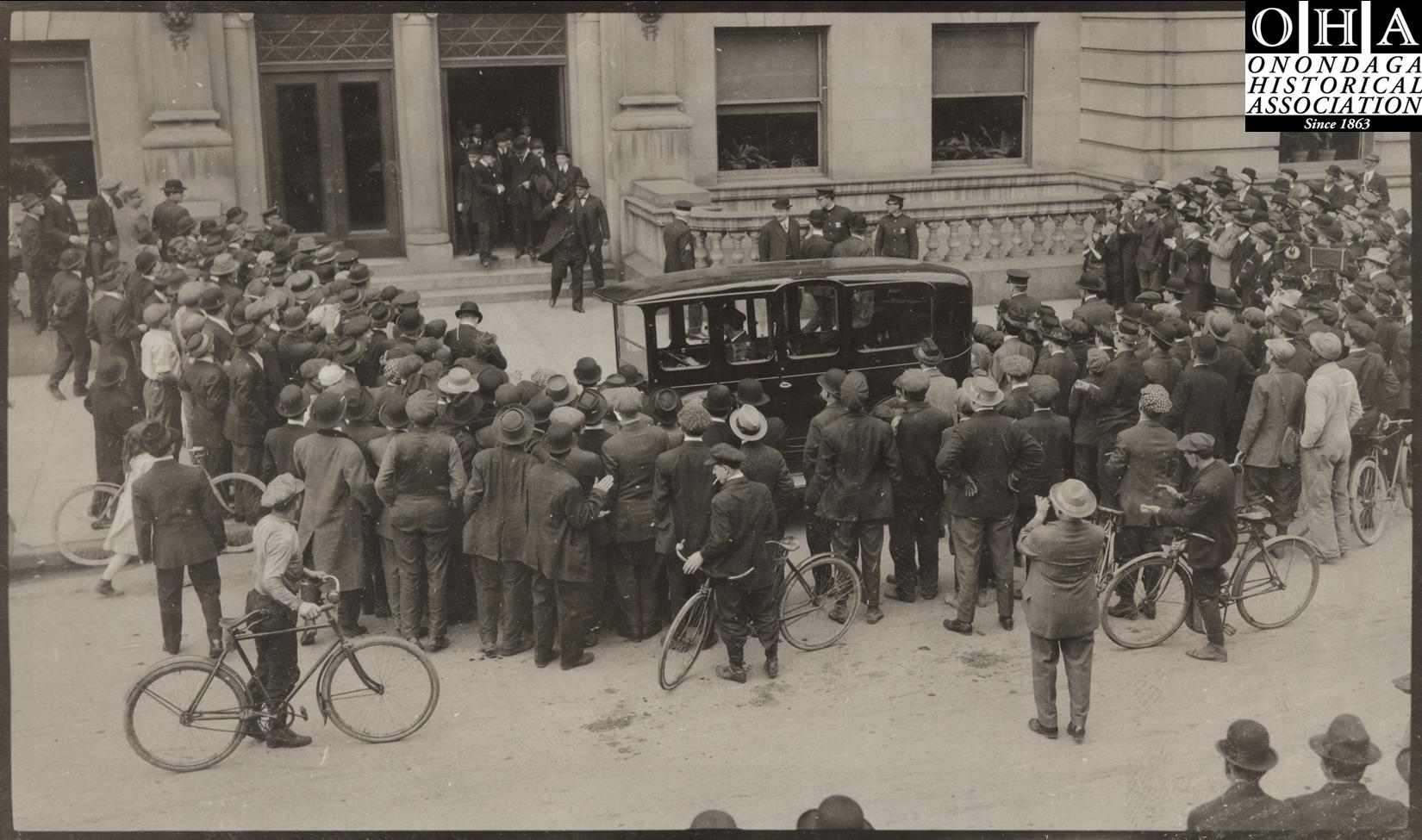

When jury selection finally began on April 19, photographs of the contestants and their attorneys arriving at the courthouse filled the front pages. The accompanying news items detailed the crowd’s shouts of “Hello, Teddy” and “Hello, Colonel,” the smile “flashed in return,” and “click, click of the Kodaks” as the Roosevelt entourage made its way from the Onondaga Hotel. The early edition of The Journal on the 19th ran a front-page story headlined, “TWO PRINCIPALS KEEN ON SCANNING MEN IN THE BOX,” and pictured the antagonists as “silent, serious, and carefully ignoring each other.”

On the previous evening, The Herald had even featured a piece about one of T. R.‘s Rough Riders, a Captain Jack, who had come to town to “see the Colonel” and had been deprived of $70 at the Yates Bar. “It was a mean thing they done to me, but I’ll get along somehow until the Fourth of July when I draw another pension,” he told the reporter. It was easy to overlook the bigger battle raging in Europe and the news that the British had sustained heavy losses in attempting to destroy Germany’s position southeast of Ypres. Few would have noticed the United States Supreme Court had just decided that Leo Frank must hang for the murder of Mary Fagan.

From the beginning of the jury selection, the scene at the courthouse had taken on the aura of a political nominating convention. Congressmen, State Senators, Assemblymen, party leaders and a former Governor greeted each other in the courtroom and huddled in earnest conference in the corridors. Many of them were on the witness list. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Alfred E. Smith, and Harvey D. Hinman, among other notables, would eventually testify. Outside the courtroom, special telephone lines had been installed for the use of the country’s top political reporters. Folding chairs had been arranged in tight rows along the courtroom walls to help seat the fortunate few who held the special yellow tickets required for admission.

From the beginning of the jury selection, the scene at the courthouse had taken on the aura of a political nominating convention. Congressmen, State Senators, Assemblymen, party leaders and a former Governor greeted each other in the courtroom and huddled in earnest conference in the corridors. Many of them were on the witness list. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Alfred E. Smith, and Harvey D. Hinman, among other notables, would eventually testify. Outside the courtroom, special telephone lines had been installed for the use of the country’s top political reporters. Folding chairs had been arranged in tight rows along the courtroom walls to help seat the fortunate few who held the special yellow tickets required for admission.

In 1915, a frequent source of entertainment for the upstate populace was watching their favorite trial lawyers in action. Trials were a show. The “best” lawyers were the best showmen. Barnes’ attorney, William J. Ivins, it was certain, would please the crowd. The newspapers had often described him as one of New York’s most renowned courtroom performers and a “sarcastic and merciless” cross-examiner. A

former Army Colonel in his middle sixties, dressed in his habitual courtroom attire of gray suit, gray spats, and skull cap, he had the sardonic manner and the aquiline look befitting his newspaper image.

Roosevelt’s chief attorney was John M. Bowers. Tall, impeccably dressed, with neatly trimmed beard and moustache and wearing black ribboned pince-nez glasses, Bowers looked something like Senator Henry Cabot Lodge. He appeared to be what he was: a courtly senior partner of one of New York’s finest firms. While Ivins was sometimes brilliant, often combative, and always unpredictable, Bowers was cool and consistent, projecting lucidity and competence.

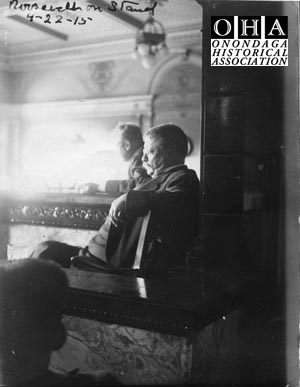

The testimony started with the words, “Mr. Roosevelt, take the stand.” Ivins, in one of the surprise moves for which he was known, created a stir of excitement by calling the defendant as his first witness. Surprised or not, Roosevelt rose with no hesitation and – with the aplomb of an accomplished actor- walked to the witness chair to be sworn. No one doubted that he knew that this was his show and that he was the star performer. Ivins posed the few questions needed to prove that the defendant was the author of the statements and that they referred to the plaintiff. He rested his case. The defendant’s case began immediately. Roosevelt remained on the stand for eight days as Bowers first and most important witness.

For the most part, the performers lived up to their billings. But the script today would seem mundane to audiences grown accustomed to the sensational political scandals of recent years. To be sure, Bowers showed that Barnes had teamed up with Murphy and Tammany Hall, at the urging of the “moneyed interests,” to block reforms such as the franchise tax bill, the bill to abolish horserooms and the Hinman-Green bill championed by Governor Hughes to establish direct primaries. (In his opposition to direct primaries, Barnes, according to Roosevelt, had made some ill-advised references to the voting public as “riff-raff,” a telling point with the jury which the defense kept emphasizing, to Barnes’ obvious displeasure.) And Bowers made much of Barnes’ dispute with Roosevelt concerning the incompetent Superintendent of Insurance, Louis F. Payne, during Roosevelt’s governorship. (Barnes had allegedly pandered to the “moneyed men” by keeping Payne in office over the Governor’s objections and the protests of the reformers.) In addition, Bowers demonstrated that Barnes had used his political influence to gain profitable printing contracts from the State. But the proof fell far short of portraying Barnes as an evil man or the blatantly cynical politico who reportedly had said about an upcoming political appointment: “I want a candidate for this office who is down and out, on his uppers, and has fringed clothes, then I can hoist him into office and he will be mine.”

The star performer saved the show and held his audience for the full eight days. The witness chair had become a “bully pulpit”; the witness was irrepressible. To Roosevelt, there was no question that as a former President of the United States he should be permitted to participate fully in the colloquies between the court and counsel. It could hardly have been expected that he would have been much in awe of the court. After all, he and Justice Andrews had known each other as classmates at Harvard. On the stand, Roosevelt gesticulated, orated and, ignoring the lawyers and the court, simply said what he wanted to say. The frustrated Ivins objected frequently, but to no avail, and even the Justice’s gaveling couldn’t stop him.

The long awaited confrontation on cross-examination between the voluble witness and the merciless inquisitor produced few of the hoped-for sparks. As one would expect, Ivins was careful, very careful.

He tried to embarrass Roosevelt by showing his relationship with Thomas C. Platt, at one time the top Republican in the State and known as the “easy boss”. His point was that Roosevelt, who professed to hate all bosses, cleared every important political appointment with Platt. Ivins developed that T.R. even consulted the “easy boss” in deciding whether to run for Vice-President on the ticket with McKinley in 1900. He also scored some points in his questions about the connection between the large political contributions to Roosevelt’s 1904 Presidential campaign from U.S. Steel’s Henry C. Frick and Elbert Gary and his tacit approval in 1907 of U.S. Steel’s acquisition of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company.

The case closed with stirring final summations to the jury by Ivins and Bowers. Bowers argued that Barnes was trying “to destroy Theodore Roosevelt’s usefulness to the People” and that only the jury could prevent this loss to democracy and preserve any chance for political reform. “Stand for him, stand for the People” he pleaded. He finished by reading the Gettysburg Address.

The jury, after hearing over one hundred witnesses in almost five weeks of trial and deliberating for two days, reported its decision on May 22, 1915. It was a unanimous verdict for the defendant. Barnes’, not Roosevelt’s, hide would go on the fence. Barnes’ career as a political leader had ended. The trial ruined any chance that he might have had for a seat in the U. S. Senate and his influence decreased steadily thereafter.

Roosevelt made the most of his victory and bragged that democracy had triumphed over the machine. To his chagrin, however, the case had disappeared from the front pages of The New York Times. With the sinking of the Lusitania on May 7, the country’s attention had turned to events in Europe. The victorious defendant’s attempts to have the trial transcripts published for mass circulation failed for lack of interest.

The Colonel’s political star regained some of its luster, however, and there were brief rumors of a possible presidential nomination in 1916, and again, in 1918 some talk that the Republicans might turn to him as their candidate in 1920. But Roosevelt died in January 1919, less than four years after the trial, his ambitions for a return to the political limelight unrealized. He was 61 years old. Most Roosevelt biographies have either ignored the Barnes-Roosevelt trial or mentioned it only in passing. But it represents a significant event in the political history of New York and the nation, and provides a poignant picture of the ex-President near the end of his distinguished career struggling to reclaim his former power.