Gustav Mahler (left) was born on July 7th, 1860 in Bohemia, Austrian Empire. Mahler was a composer and conductor, noted for his 10 symphonies and various songs with full orchestras. Although his music was largely ignored for 50 years after his death, Mahler was later regarded as an important forerunner of 20th-century techniques of composition and an acknowledged influence on such composers as Arnold Schoenberg, Dmitry Shostakovich, and Benjamin Britten.

Gustav Mahler (left) was born on July 7th, 1860 in Bohemia, Austrian Empire. Mahler was a composer and conductor, noted for his 10 symphonies and various songs with full orchestras. Although his music was largely ignored for 50 years after his death, Mahler was later regarded as an important forerunner of 20th-century techniques of composition and an acknowledged influence on such composers as Arnold Schoenberg, Dmitry Shostakovich, and Benjamin Britten.

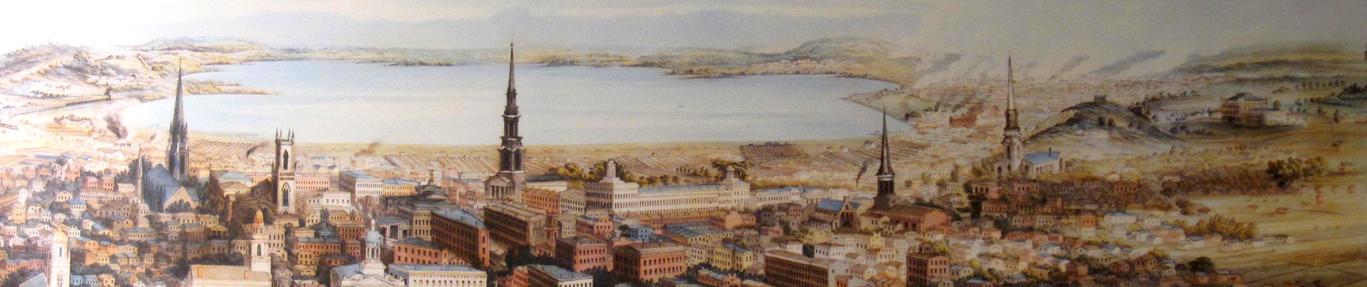

Late in his life, Gustav Mahler visited Syracuse on a tour of New York. He and the New York Philharmonic performed at the Wieting Opera House on Dec. 9, 1910. The concert hall sat on the south side of Clinton Square, on Water Street, in Syracuse. Over the years, there were four Wieting Opera Houses at this site. The last Wieting, dating to 1897, held 3,000 seats.

The following review appeared in the Syracuse Herald on Dec. 10, 1910, under the headline “Grand Concert of the New York Philharmonic.” Its spelling and punctuation are as they appeared in the original. (Original post via Syracuse.com)

“From the musical point of view, the orchestral concert of the New York Philharmonic society at the Wieting last night will rank among the great successes of its kind in the musical history of Syracuse. As a business enterprise, be it said with regret, a similar claim cannot be made for it. An entertainment of this superlative character deserved a crowded house. As it was, the audience was of only moderate size, say, of the third-night standard for a popular play. For this the blame cannot fairly be attributed to the music-lovers of Syracuse, who on two occasions last year filled the theater at symphony concerts. It must rather be charged to an error of judgment on the part of the management of the Philharmonics’ tour, which established a scale of prices for Syracuse that at once excited resentment and repelled patronage. With a $2 maximum for admission, a reasonable one even for so grand a performance in a city the size of Syracuse, the seating capacity of the opera house would probably have been exhausted. From the pecuniary viewpoint, it was an unwise venture to advance arbitrarily the schedule for choice seats. The mistake was specially deplorable inasmuch as it was the means of keeping the local reception to Gustave Mahler and his accomplished artists within limits that fell short of their deserts.

But this was the only subject for regret or adverse criticism in connection with a concert that will long be recalled with profound pleasure and satisfaction by all who were privileged to hear it.

No small part of the public interest aroused by the appearance of the New York Philharmonic orchestra was directed to its famous conductor. Herr Mahler is short in stature and slight in build, and seemingly the very incarnation of nervous energy; and yet he is less eccentric in motion and lavish in gesture than the average maestro of his rank. One would say that his magnetic influence over his orchestra is that of the mind rather than of the physical man, for his leadership is clearly more thoughtful than demonstrative. His orchestra differs from others of equal celebrity that have appeared here in recent years, not only in the superior number of instrumental voices and the more marked preponderance of string over wind, but also in a finer precision of sheer technic, as, for example, in the rigorous uniformity of the bow movement among the first and second violins. Herr Mahler’s strings are a magnificent aggregation of trained performers, and their work is perhaps the best example ever furnished in Syracuse of the unequaled adaptability of the king of instruments for all the variations of musical expression.

The program was something more than a classical feast. It was, in a broader aspect, a historic review — an educational study of orchestral composition in three stages of its development. The first number took the auditors back two centuries, to the days of old Johann Sebastian Bach, who with his harpsichord and strings and double-reed accessories, the primitive oboes and bassoons, laid the foundation of the present-day orchestra. From two of Bach’s earlier compositions of this class, Herr Mahler has adopted a suite for the modern orchestra, which delighted the ears of his listeners last night with its archaic simplicity and touches of real genius, the whole quaint effect heightened by his own performance on the harpsichord.

Between the dates of Bach’s compositions and the golden age of the Shakespere of music nearly a century elapsed, and Beethoven’s “Pastoral Symphony,” played last night, as the second number on the programme as well as in the chronological order, reveals to us the perfect fruit of that master’s inspired faculty of musical invention. Beethoven always protested that his symphonies were intended to be suggestive rather than definitely descriptive in their awakening of emotions, and the distinction he thus makes is admirably illustrated by his Fifth symphony, indicative of Fate knocking at the door. Yet the Pastoral symphony, both in the andante and the final movement, is in an appreciable degree real delineative music, with its subtle imitations of some of the nature’s voices and its stirring simulation of the swell and break of a summer storm. But the master’s power of suggestion has full scope, too, in his instrumental reflection of the glory and repose of the picturesque countryside and of the innocent merriment of rustic life.

The three Wagner numbers of the programme, bringing us fifty years nearer to our own day, and representing the last important work in orchestral evolution, completed the contrast and closed the historic retrospection. They were grouped with superb judgment to illustrate three phases of the Wagner contribution to musical art — its tragedy, its romance and its refined comedy.

In its interpretation of Wagner, the orchestra was technically at its best. It was a brilliant exhibition of artistic skill and enthusiasm and an eloquent tribute to the breadth and profundity of Herr Mahler’s directive power. But the supreme delight of the evening was its masterly reading of the Beethoven symphony. The exuberant and versatile fancy of the greatest of all musical composers, with all its wealth of imagery and beauty of melody, was never before made articulate in Syracuse with such fervor and accuracy of execution as the Philharmonic devoted to it last night. If it was not perfection itself, it was so near perfection that the trained ear and mind that could detect a shortcoming must have been abnormally acute and sensitive. While the whole programme was rendered with consummate ability, the Beethoven symphony will linger longest, we believe in the memory of last night’s audience.”