The United States has been, and remains, a nation built of citizens from a variety of ethnic backgrounds, striving to achieve the “American Dream” of financial success and social acceptance. But often, the reality of that dream requires citizens to become less diverse and a bit less distinct, to become what is accepted as a typical American.

This effort to achieve acceptance and equality can create dilemmas – what does a citizen retain of his or her distinct heritage and what can be abandoned to be more accepted?

Every ethnicity has faced this, from the original Native Americans to the most recent immigrants. It also can challenge an entire ethnic community as it debates the necessity, methods, degree, and pace of that assimilation.

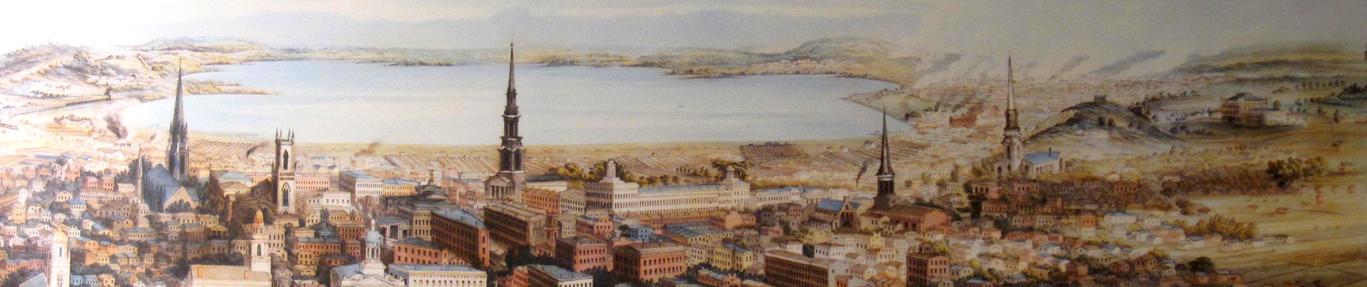

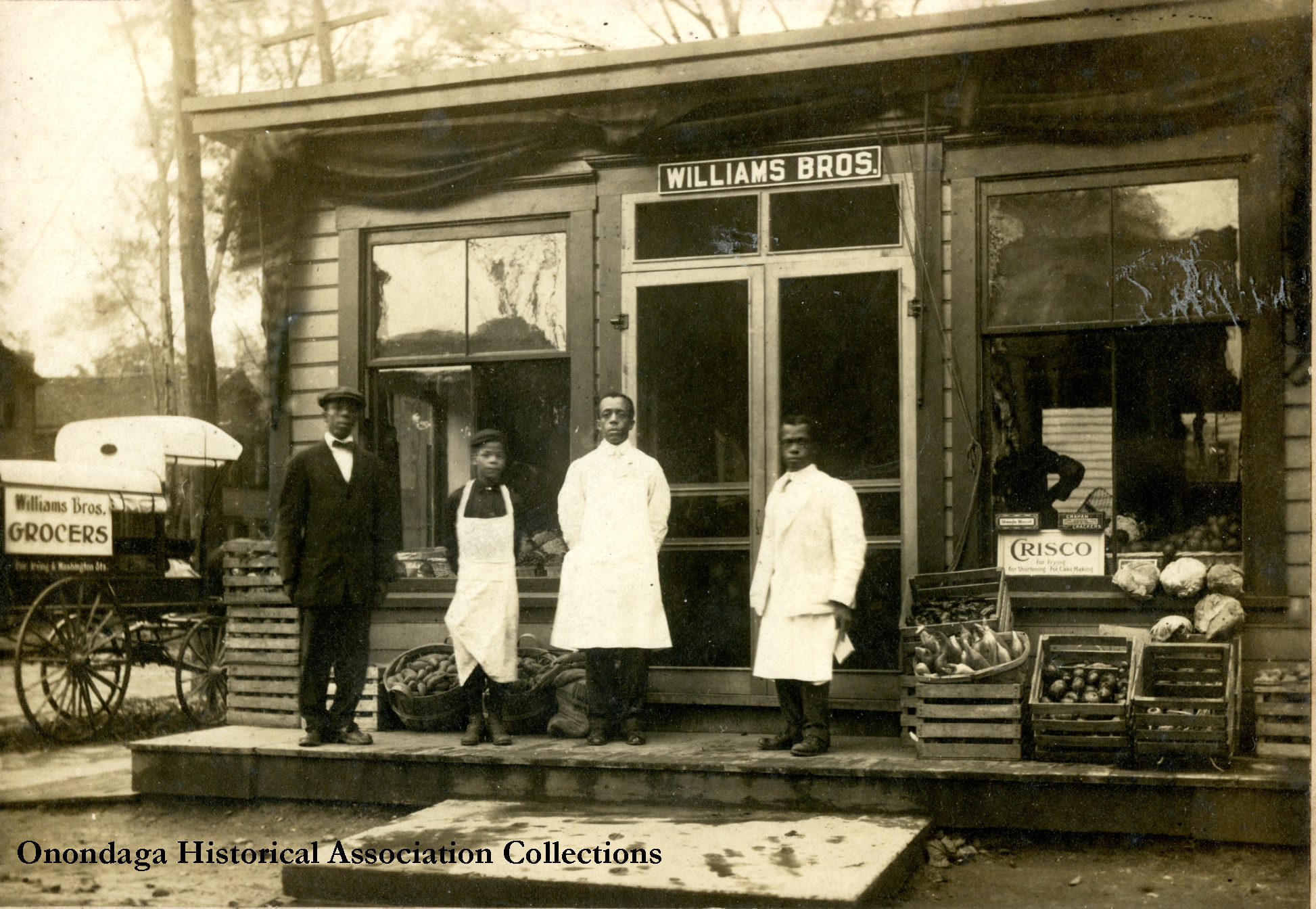

Often, that heritage is embodied in an ethnic neighborhood. For Syracuse, the African-Americans lived and worked in the 15th Ward.

For most of the 19th century, there were a small number of African-Americans in Syracuse, many living north of East Genesee Street near the first AME Zion Church. As African-American numbers increased toward the mid-20th century, widespread discrimination led to their almost exclusive concentration in the 15th Ward, the area immediately east and south of downtown. Mrs. Luana Adams recalled:

“When I first came here it was just as bad as it was in Georgia. Here, the colored lived nowhere but in the colored town. And they didn’t want you no place.”

But this neighborhood holds bittersweet memories for a generation of older African-Americans. Otey Scruggs, an African-American professor of history at Syracuse University, wrote the following about life in the 15th Ward before the Civil Rights era of the 1960s:

“The Ward, however, was a refuge from discrimination [found elsewhere]. Social cohesion was provided by clubs, churches and the Dunbar Center, the most prominent community institution. But most of all, the ties that bound rested on the camaraderie that blossomed from knowing virtually everyone in the community.”

“The Ward, however, was a refuge from discrimination [found elsewhere]. Social cohesion was provided by clubs, churches and the Dunbar Center, the most prominent community institution. But most of all, the ties that bound rested on the camaraderie that blossomed from knowing virtually everyone in the community.”

John A. Williams, an African-American author who grew up in Syracuse’s 15th Ward, wrote in 1964 about a facet of that camaraderie:

“If both parents were away at work or shopping, you could bet your life that some old man whittling on a stick had their eyes on you. If you misbehaved, the folks had the report as soon as their feet hit the steps. Ours was a community, despite everything else, in which survival of the other fellow or his children mean survival for yours.”

In 1950, almost 4,000 African-Americans, eight of every nine in Syracuse, lived there. By 1960, the African-American population reached 11,210, a 144% rise. But black citizens comprised a little over 5% of city residents and lacked political influence.

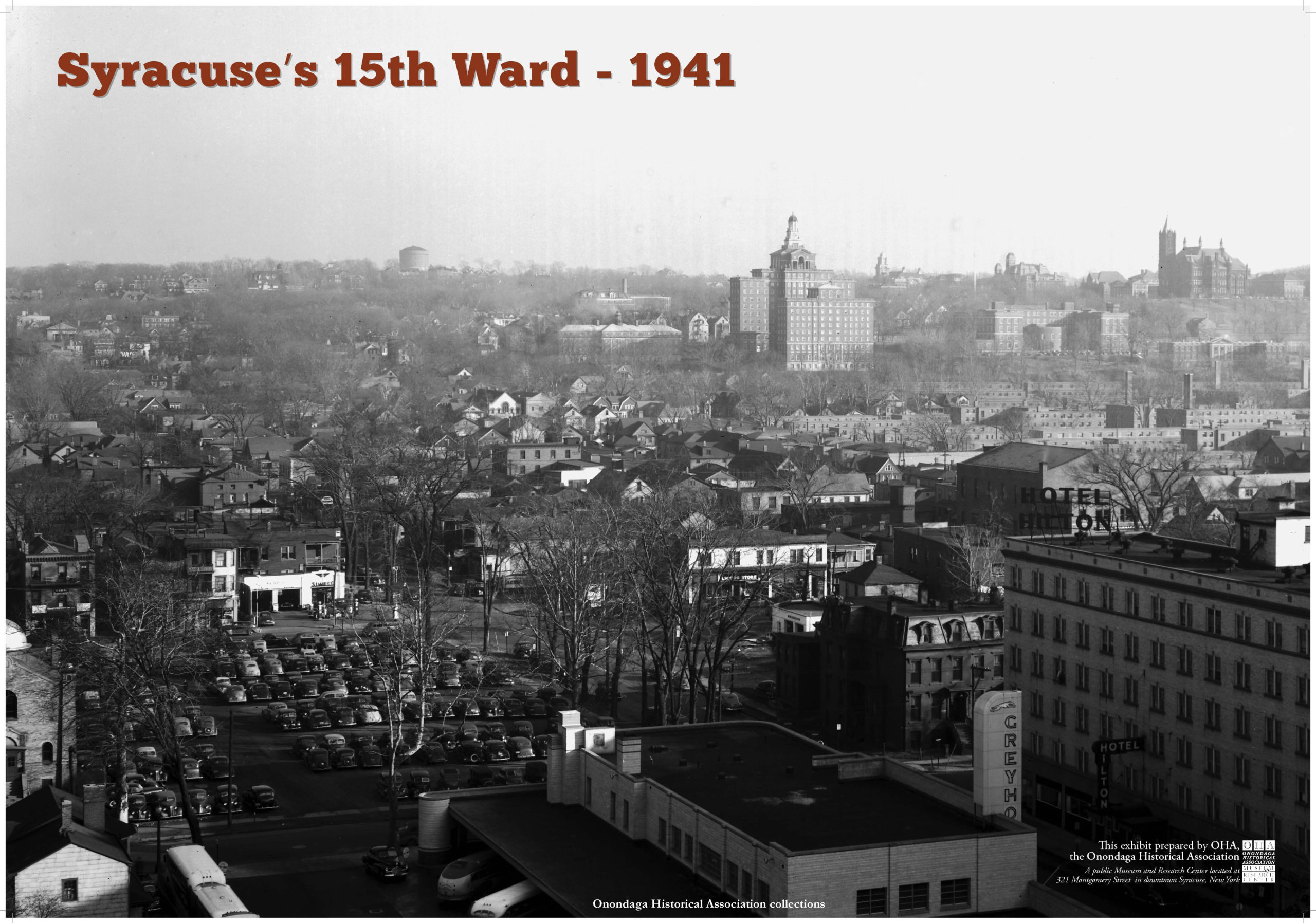

Syracuse’s Urban Renewal plan called for the area between State Street and Syracuse University to be re-born as a government complex, cultural center and high-rise residential neighborhood. In the way were the overcrowded “slums” of the 15th Ward, much of it substandard housing. City planners felt it would be a blessing to eliminate them. Over 27 blocks were targeted, impacting 75% of the local black population, a population that would need relocation.

African-Americans, long suffering the discrimination that pushed them into the district, first hoped the plan would lead to better housing and more city-wide integration. It was that dream, it seemed to many, that might be worth the loss of the 15th Ward’s beloved black institutions and sense of community. But it soon became apparent that most other city neighborhoods were unwilling to accept African-Americans. Relocation efforts began to lead most African-Americans into other run-down, older neighborhoods south and east of the 15th Ward.

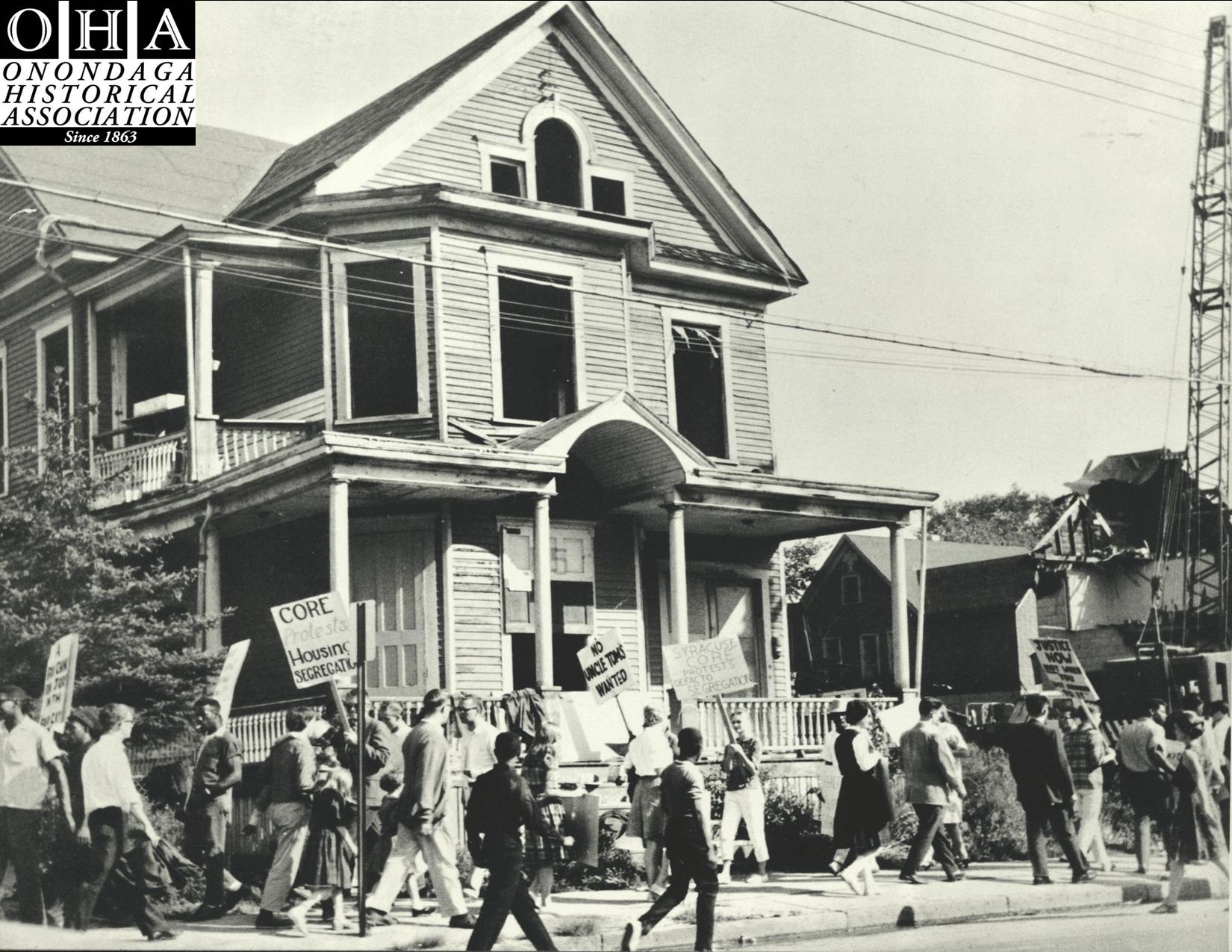

The 1960s was also a time of growing civil rights activism. Local African-Americans, long denied political influence, debated how to respond. Some advocated protests to pressure city hall into finding better housing, Picketing and sit-ins were held at demolition sites in 1963. Dozens of arrests were made. Set against the national civil rights protests in the South, it was sometimes viewed negatively by the local establishment, as agitation by outsiders. But African-Americans also sought to influence the system from inside and the decade saw the first African-Americans elected to local political positions.

It was a critical decade for local African-Americans as they struggled to find the right balances:

- Between cooperation and protest, to achieve political influence and recognition

AND

- Between demolishing and preserving your past, for a chance to improve your lives.

After the Civil War, Syracuse’s small African-American population stayed loyal to the Republicans, the party of Abraham Lincoln. But this loyalty, along with their minor voting numbers, meant they were usually taken for granted by party leaders and kept on the margins. But the early 1960s brought major changes.

- Large migrations from the South for jobs increased the local black population

- Nationally, the civil rights movements gained visibility and momentum

- Syracuse University faculty and students began to identify with the civil rights cause

- The massive residential relocation of the East Side Urban Renewal project brought the issue of housing discrimination to the forefront in Syracuse

The local black community sought to find effective leaders and tactics. Many debated how best to motivate the white political and business leadership to make changes. Some advocated confrontation like CORE (the Congress on Racial Equality). Others sought a more patient approach through organizations such as the Urban League.

Despite these challenges, the black community increasingly made their concerns about discrimination visible. Local civil rights groups like the Urban League and the NACCP made progress in their goals. Black ministers lent their moral support and slowly, leaders emerged to engage directly as elected officials. Their struggles laid the basis for the many African-Americans in leadership roles throughout the community today.

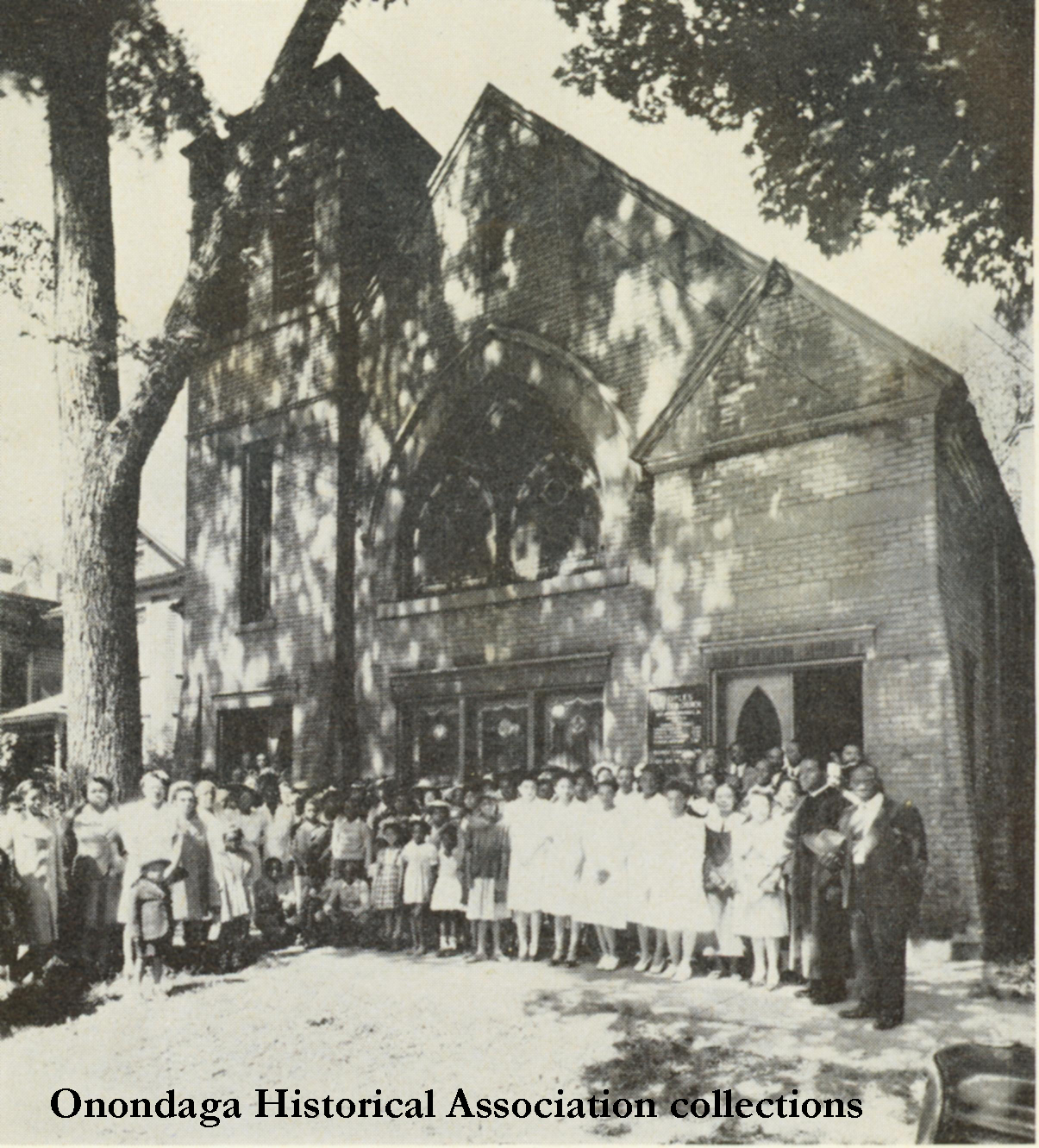

AME Zion Church 1941

Syracuse’s Urban Renewal plans for the 15th Ward called for the demolition of many of the buildings that had become familiar “landmarks” for the local African-American community. To many African-Americans, it seemed a difficult sacrifice, but perhaps necessary to secure better housing and racial integration across the city. The picketing in 1963 was aimed at achieving that vision, not to preserve potential historic sites.

Nationally, historic preservation before the 1960s had focused primarily on preserving landmarks associated with famous white men and their deeds. In Syracuse, there was virtually no historic preservation activity until the late 1960s. And until very recently, there was little recognition for local buildings associated with black history.

Surveys over the last few years, especially ones tied to early African-American history in Syracuse, have shown that most of those buildings have, unfortunately, long been demolished.

The historic AME Zion church on East Fayette Street, erected in 1910, is the only standing structure originally built for the city’s oldest African-American church, whose roots date to the 1830s. Its congregation, led by Jermain Loguen, was active in the Underground Railroad. During the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, it was equally committed, including the work of its pastor – the Rev. Emory Proctor. Although members now worship in a larger South Side church, AME Zion still owns the Fayette Street building and is working with other community groups to preserve it.